PM Pope – “The Future Filter of Abstract Minimalism”

how to give a voice in another’s voice?

a wolf voice a coyote voice a river voice

a hedgehog voice. how to give a song

to the coyote song the red wolf song

the curlew song. how to give a voice

to the river song the mountain song

the earth song the you song the me

song the without the earth voice of

coyote song wolf song hedgehog

song without the mountain song

the wild mountain thyme song

sand dune song

song the seal

song the toads

song the you

song the me

song the

then.

who

are we?

– Geraldine Green

Status Report 133

I keep saying

we’re all just different crazy.

I got a lot of cracked dishes

work just fine.

– Smith

I’ve Never Seen The Color Of Her Eyes

She’s a crime, and I am a crim

inal. She sits and waits for me to be a

lone. I sit and wait. Marcia is her

name. She sits a lot in the home for the dis

abled. Every once a year she hits pa

trons for looking at her, and she hit

s me for laughing at her sweet ass.

Marcia is yellow and should be na

med Ling Ling. But she was born her

e and never recognized she looks like a

lady from another country. I fell fo

r her when I was institutionali

zed for running a red light back in

48. I am fine now except in a car.

– Daniel Gallik

“She’s Golden” by Bree

Modern Love

So many women are wishing

their Moms happy birthday

and they’re dead. Facebook

is getting personal in a dumb

way. Pics are put on the site.

It’s not even cute. However,

none are so sad they make me

cry. One had her mom

dressed in jeans with a crown

upon her head. I guess she

thought it was so, so cute. I

wrote to her and told her to quit

it. She wrote back and told me

to shut up. (Hey, I kept the note

private.) She wrote online

that some creep was making

fun of her mom — that, “what

did I know about love at all!”

– Daniel Gallik

“Past Imperfect” by Smith

“Edgewater and 117” by Sam Hubish

“Future” by Smith

Sam Philips’ Dad and Brother at Tremont Bar in the 50s

“Spring Will Come Again” by Smith

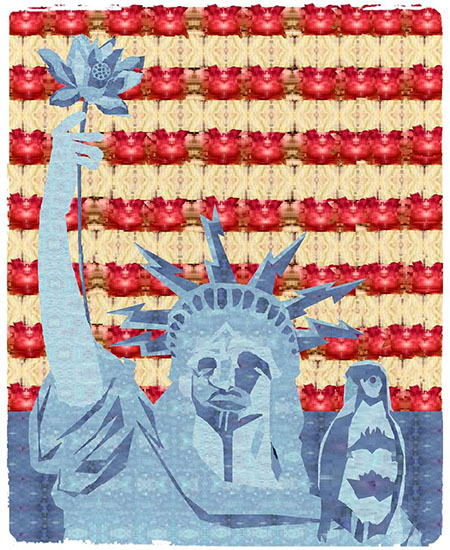

“Lotus Pray” by Bree

Status Report 140

Happiness is a cat

slow stepping on a plush blanket

soft unfolded

to dance the cat dance of press press paw paw

purr so pure it’s heard across the room

in step purr sway

step purr sway

tail slow wave

purr please

eye squeeze tight

narrowing in pleasure

of slow pad pad left

slow pad pad right

claws low nick

prick

– Smith

Status Report 157

The falling snow muffles sound, scatters night

reduces here and now to black and white

In this low light

cellophane shards shimmer like jade

– Smith

Photo by Dan Gallik

“Cat Moon” by Heather Ann Schmidt

Yardman works in the starlight

twinkling thoughts like wives’ eyes

switch on lines in rhythm with his heart

signaling dawn, “lo-ove, lo-ove,” loaded

like a train faintly blows

– Lady

Linda

There are no voices,

but a beat. Linda told me

the news is better to watch,

not to listen to, that I will

keep my mental health

if I listen to only her.

I asked her for an apricot.

She said she would go

to the store soon, and

buy me just one. I said

I needed her quickly

to improve my health.

Linda went after the news,

after dinner, after her

favorite game show,

after the abundance

of time she took to wash

the dishes and other things.

– Daniel Gallik

Photo by Jim Baron

Status Report 91

Female bees getting ready for winter

kicking males out of hive to die

and moving upper honey down to lower frames

all male drones do is sex the queen

and guzzle honey

and winter is long

– Smith

Sunlit Gathering

For one captured moment

each tall tree stands

wearing a bright yellow dress.

– Mary Weems

Excerpt from The Puzzle

by Lady

They walked onto deck, getting outdoor draughts of air, clarity, the scene. Far off details looked mostly shades between black and white, the island a solid ridge of dark gray in floating white sky and water. Subdued, quiet ocean. Hill felt an excited fraughtness, reveling in novelty. Although there’s everyday artistry in the gifts of what eyes give, Christmas imbues everything with resonance.

Hill heard jingling behind him. A rat was pulling strings of bells, thousands of small gold bells from a capacious gray bag. He pulled the strings apart delicately unthreading a mess. Hill saw it was actually strands of bells hanging from one string. It must have been hastily packed into the bag when the previous holidays were over.

The rat strew the garland of bell from hooks on a gray rowboat. It was lifted over the side. Rats ported several large baskets to a large rat standing in the boat down below. A gray rat hoisted his legs over to ladder, a bongo drum rolling over his back, loosely strapped.

Rats smiled and nudged the children to the ladder. A rat crouched down and asked of Bea, “I’m going to give you a rat ride. Put your arms around my neck and hold on tight.”

The thousands of gold Christmas bells tinkled with dip and lift of oar. Most rats were clothed against cold in brown robes and maintained the solemnity of monks. Tsi-s-de-tsi’s attire a long wool coat reaching to her feet. The coat was decorated in sophisticated black, tan and white Native American patterns.

Nearer the boat the water lost its far-off whiteness. The oars looked under clearness as they dunked under. And deeper down water thickened to opaque turquoise. The actual distance from surface to ocean floor was a mystery.

They drew themselves in and in to a cove. Tones which had been lost in gray smear thinned to contrast more strongly with each other. Outlines of blue pebbles interspersed with sand manifested to define an ocean floor, which became clearer and clearer nearer and nearer until it lost the blue.

The shore looked a static scene, mineral versus water and sky, a black and white movie. As eyes focused, stippled movements could be discerned in the static, verticalness tucking and adjusting itself. Penguins stood in stands like short, expansive groves arrayed on footprints in the sand.

The rats let the boat park itself on shore in a rough and muted whush over sober sand. Two stood and got off to make room for the rest to disembark as orderly as could be managed. Bea and Hill picked themselves up over the wooden benches, childweight light as the hollow bones of birds in comparison to the large warm mammal rat bodies.

Hill ran to the nearest group of penguins and halted. Then he laughed and half ran, half skipped to the side yelling “Hey, hey!” at the birds, fingers splayed in play. Then he realized he wasn’t sure what he was seeing. He bent down, mouth open in intent study of the unexpected: an enormous bulge at the bottom of the belly on most, a furry bulge with an egg peeking from its underside.

Bea walked forward. “Hill! Hey Hill!” her words cracking the anonymously listening beach, a black and white movie. Hill ignored her until she came right up to him.

“Beatrice, they have eggs,” he said in a young boy’s insistent voice. “I wonder why they have those eggs. Do you know why they have those eggs, Beatrice?”

“I guess they’re their babies.”

Unbeknownst to Hill and Bea, a contingent of rats was busy at their backside, harvesting eggs into baskets. They lifted up penguins who snapped at the robbery. An occasional rat took an egg, poked it, and swallowed its semi-liquid contents down the hatch. (What can you do, a rat’s got to eat.)

Tsi motioned her paw sharp and quick to indicate enough. “We don’t want to disrupt this ecosystem,” she scolded.

At the words Bea and Hill looked back.

Rays of white low horizon sun sprinkled through a thinness in the clouds as though an expansive strum of gilt harp, and the air was quiet except for subtle repeating reaching and receding waves.

Tsi-s-de-tsi was at the boundary of their section of enclosed scene, nearer the water. The rats were stacking their baskets of penguin eggs into a neat pile. There was a humanity to their need to eat practically.

Their brown monk robes juxtaposed with their animal features, their fuzzy, soft rat heads, the alienness of their beady eyes. But they were real and aware despite their animal interface, and accessible via the exchanges that words make.

(The practicalness of rats: rats line their nests. They steal money, paper money, and they chew it up, and line their nests with it. Although for a six foot rat it would take a lot of money, wouldn’t it.)

A six foot tan rat with whorled hair poured coffee into the metal cups of those who wanted, standing. A squat white rat with a kindness to the stoutness of its face looked at Bea and Hill and nodded up and down, said “Coffeeee….. coffeeee,” then nosed open a basket to retrieve two cups.

The children sipped the bitter liquid of adult mystery as though they were supposed to. Light reflected off the ocean.

When everyone was through, they walked a cold and straggled flapping line inland up shallow tables of rocks. Bea held Hill’s hand into the heaven of it, their arms a swinging V. The coffee amplified a realization of happiness.

The bongo rat trailed at the rear slowly drumming “BUM, bum BUM.. BUM bum-bum BUM.” It droned them into the thick of a mystical consciousness.

There were no trees, no shrubs, no grasses. There was brown and green and yellow lichen dry over large rocks like splattered dried sea brine. A plant of cold and colorlessness.

At the flatness of some later altitude the rats seemed decidedly finished, some sitting, even. The children went over to some rats who felt more like family and snuggled in their sheltering robes. Tsi came over like a wise woman and pulled a paw from pocket, a little leather book decorated with a gold title, “The Book of Knowledge” in anachronistic Times New Roman.

“This is for you, Beatrice, on this Christmas morning,” and she put the old book new into Bea’s curious hands.

Tsi defted her paw into her other pocket to pull up shiny silver tinsel of a necklace. “And this is for you, Hill.”

Hill held the necklace’s large flat shiny pendant mittened between his thumbs. It was a puzzle piece. He opened his mouth in study, yet unsurprised. His breath came out inner wet warm and his breath came back frozen dry. His nose felt numb and ears alien and thin.

The bitter winter winds cut into the party now that they were higher up on the island, and they noticed cold from the awareness brought on by activity come to rest. The rats at least broke the wind for Hill and Bea, an almost solid dark wall of insulation.

The bongo drums became slower, meditative, the petering out of ceremony. The musician looked hep but grounded, the pink of his little round ears peeking from the sides of a brown and gold kufi hat. He sat on a rock with the pair of drums snug between spread knees. He sat straight up with formality. He’d close his eyes and nod his head to either side, listening to what he weaved.

“Cold enough for you?” asked a paternalish rat. Bea smiled and held her wool hat down against her ears. “Have some of our private stock, just for you, on Christmas. Before we go back down.”

He poured steaming hot amber liquid into two stainless steel cups and gave them to her and Hill. Bea took a small sip. It tasted like cinnamony honey, like watery thin, hot cough syrup. It was pleasant but like a burning vapor down her throat.

“Some honey for the Bea,” Tsi said. “It’s mulled mead. We have sugar in the ship, too, my hon hon honeybee. Sugar in the shelter for our baby sweets.”

They sat with the task of sipping until finished. The drummer ratta tat tatted a resolution with the flat pads of a calloused hand, and all rats stood up. Tsi pulled Hill’s scarf up to cover his nose. His mouth’s exhales were caught in a warm wetness under the cloth.

“It’ll be warmer where we’re going soon, children. Aw… it’ll be warmer. Let’s march.”

“BA dum, DUM… DAH-dum dum, dum… BA dum, DUM… DAH-dum dum, dum…” went the drums. “BA dum, DUM DUM-DUM DAH dum, BA dum, DUM DUM-DUM DAH dum.” And the party started its mystical march to the shore.

. . .

The large cheerful rowboat looked like a toy on the shore, Sicilian colors, red sides banded by white, the top of the boat saturated light blue. Gold bells of Christmas adding that much more festiveness.

Rats pushed it out a little into the water, then packed the baskets from the pile on the shore into the boat, sandy laden with penguin cargo and little curiosities, appealing little rocks to hold in one’s paw for contemplation on long winter nights swinging in a hammock.

The penguins watched the party embark to the water. One could not tell from their expressions if they grieved the robberies of some of their eggs, but one could imagine sadness in their uniform watchfulness, in the tips of their penguin wings pointed down in landed helplessness.

With the push into the cove, the bongo player tapped like a splash down, and then purcussed out commencement music that ignited the cyclical work of the oars. In the boat the music was a mystical busyness to Hill and Bea. The sky, gray again, crouched down in in heaviness that concentrated introspection.

Everything is set to music whether here or paused.

The rowboat pulled up to Veronica like a baby whale to its mother, bobbing a bit, silent now. Tired rats pulled cargo up her ladder and onto her deck. The children watched Tsi climb up the wooden rungs, her Native American black white and tan robe heavy, and her body surprisingly heavy and tired for a four foot mouse.

“You, you sit here,” said a rat whose first language was not English. Her voice sounded rough, East European. “This, sit here,” and beckoned into an extra large basket.

First Bea went up. Then Hill. He hung in the basket with his legs dangling down and kicking casually like he was wont to do, and he happy and cared for sang, his voice warbling in uncertainty and sweetness: “Row row row your boat, gently down the stream… merriwee merriwee merriwee merriwee, life is but a dream.” It was a song for the edification of the universe, to uplift it and make it remember how good things can be.